I first heard the story of Phineas Gage in 1998, during my second year at Medical School. Neuroanatomy was not my strongest suit, and I spent most of the lectures scribbling notes in a frantic haze of confusion, desperately hoping that I would be able to decipher them later. The story of Phineas Gage represented a rare moment of clarity, however, and I left the lecture theatre the day that I heard it with a clear understanding of the material for a change.

Who was Phineas Gage?

Phineas Gage was an American railroad construction foreman. He was born in Grafton County, New Hampshire on July 9th, 1823, the first of five children born to Jesse Eaton Gage and Hannah Trussell Gage.

Little is known about Gage’s childhood and early life, but it is thought that he worked with explosives on farms, mines, and quarries as a youth. By 1848, gage was 25-years-old and was the foreman of a crew cutting a railroad bed in Cavendish, Vermont.

He was described by his employers as being: “a most efficient and capable foreman… a shrewd, smart businessman, very energetic and persistent in executing all his plans of operation.”

The accident on September 13th,1848

On September 13th,1848 Gage was directing a work gang that was blasting rocks to make way for the railroad. Setting a blast required a deep hole to be bored into a rock, blasting powder and a fuse would then be inserted into the hole, and a tamping iron used to pack down clay and sand above the powder. This was a process Gage had performed thousands of times before.

At approximately 4.30 pm Gage was holding a tamping iron while preparing for the explosion. He became momentarily distracted by the men working behind him, causing him to turn around. This brought his head directly in line with the hole below. At the exact same time the iron he was holding sparked against a nearby rock and ignited the fuse. The tamping iron was propelled through Gage’s left cheekbone, penetrating his skull and exiting through the top of his head. The iron was subsequently found about 30 yards away, “where it was picked up by his men,smeared with blood and brain.”

Gage was thrown onto his back, had a brief seizure, but recovered quickly and sat up and spoke within a few minutes. Shortly afterward he stood up and walked with little assistance to an oxcart, which took him back to the town where he resided. Miraculously, Gage has somehow survived.

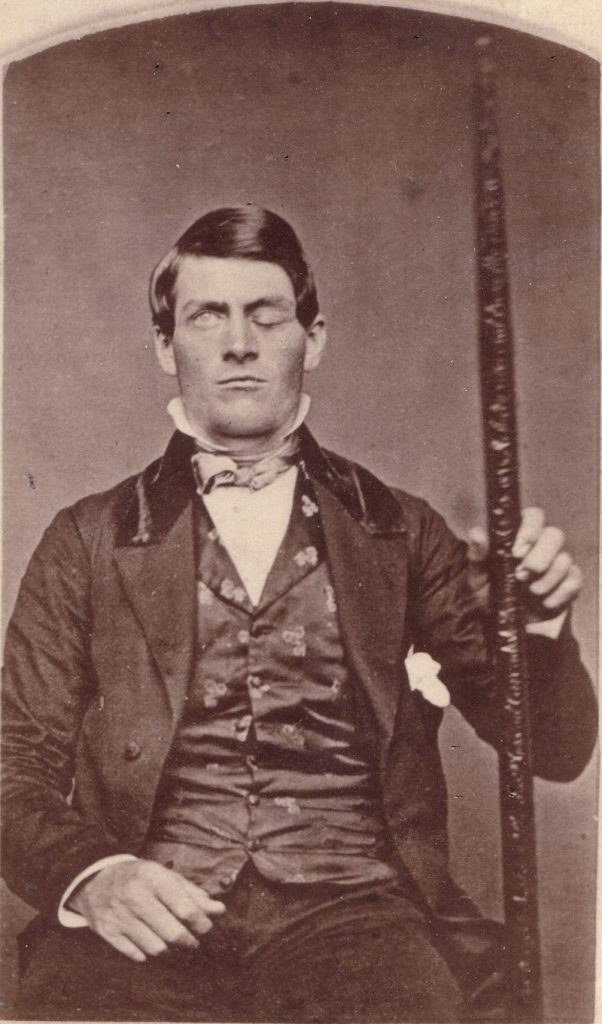

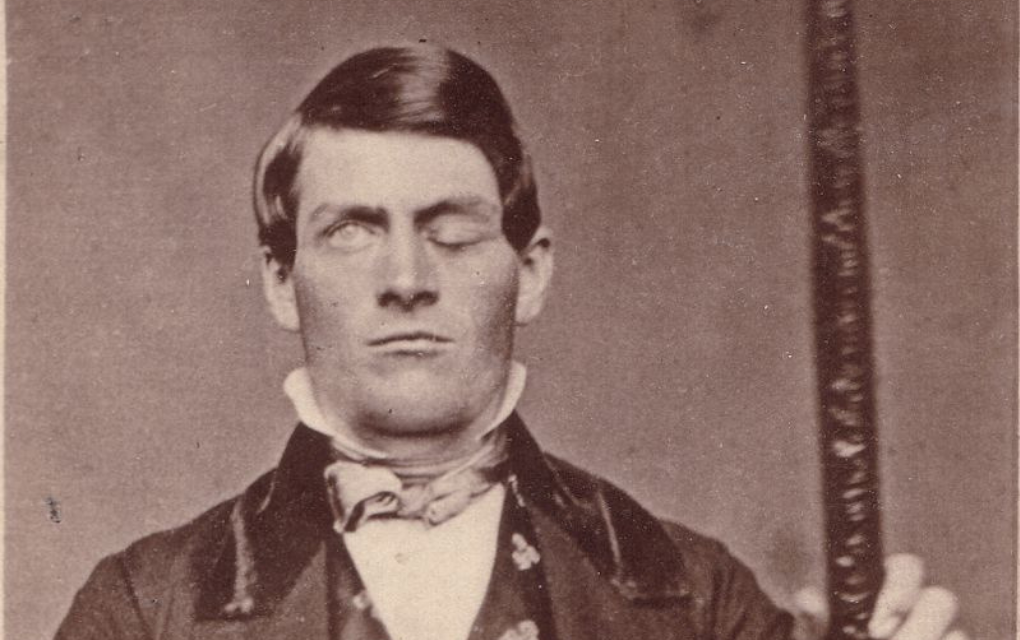

Phineas Gage posing for a portrait with the tamping iron

Doctor, here is business enough for you

About thirty minutes later a local doctor, Edward H. Williams, found Gage sitting outside his hotel. Gage apparently greeted the doctor by stating “Doctor, here is business enough for you.”

Dr. Williams recalled their meeting in the following statement:

“I first noticed the wound upon the head before I alighted from my carriage, the pulsations of the brain being very distinct. The top of the head appeared somewhat like an inverted funnel, as if some wedge-shaped body had passed from below upward. Mr. Gage, during the time I was examining this wound, was relating the manner in which he was injured to the bystanders. I did not believe Mr. Gage’s statement at that time, but thought he was deceived. Mr. Gage persisted in saying that the bar went through his head. Mr. G. got up and vomited; the effort of vomiting pressed out about half a teacupful of the brain, which fell upon the floor.”

Shortly afterward the town physician, John Martyn Harlow, arrived on the scene and took charge. With assistance from Williams, Harlow proceeded to shave around the exit wound and removed clots, bone fragments, and a small piece of brain that was protruding from the area.

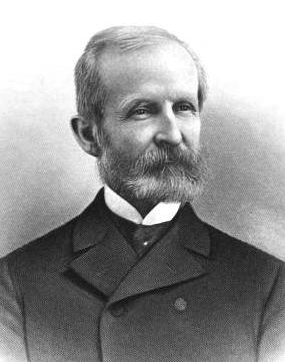

Dr. John M. Harlow

Harlow later described his findings in detail in a letter to the editor of the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal:

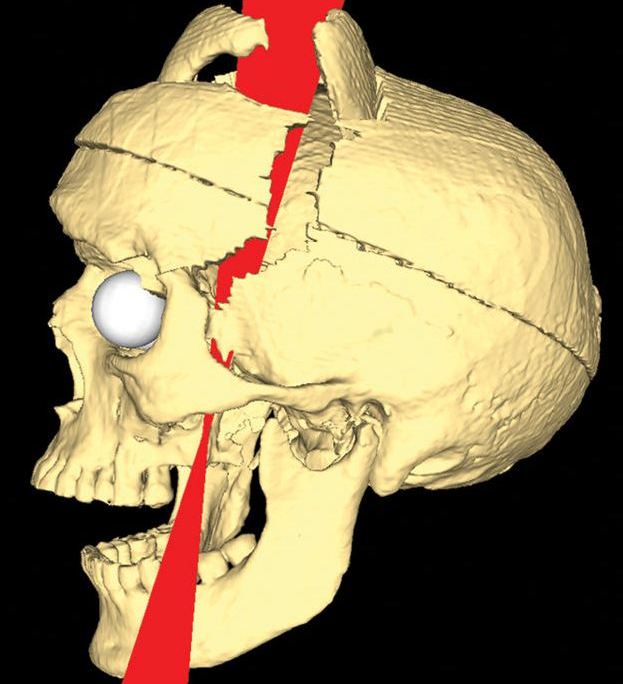

“[The tamping iron] entered the cranium, passing through the anterior left lobe of the cerebrum, and made its exit in the medial line, at the junction of the coronal and sagittal sutures, lacerating the longitudinal sinus, fracturing the parietal and frontal bones extensively, breaking up considerable portions of the brain, and protruding the globe of the left eye from its socket, by nearly half its diameter. “

Within a few days, one of the wounds became infected, and Gage fell into a semi-comatose state. His family feared the worst and made plans for his funeral. Gage went on to recover though and later that year he was well enough to return to his parents’ home in New Hampshire.

3D reconstruction of the path of the tamping iron, image sourced from Wikipedia

Courtesy of Van Horn et al. CC BY-SA 2.5

Recovery and ultimate death

Despite his physical recovery, Gage would not recover fully mentally. The subsequent changes in his personality and decision-making provided the scientific community with important clues as to the role of the frontal lobe.

In 1868 Harlow wrote a report on the “mental manifestations’ of Gage’s brain injury:

“His contractors, who regarded him as the most efficient and capable foreman in their employ previous to his injury, considered the change in his mind so marked that they could not give him his place again. He is fitful, irreverent, indulging at times in the grossest profanity (which was not previously his custom), manifesting but little deference for his fellows, impatient of restraint of advice when it conflicts with his desires, at times pertinaciously obstinent, yet capricious and vacillating, devising many plans of future operation, which are no sooner arranged than they are abandoned in turn for others appearing more feasible. In this regard, his mind was radically changed, so decidedly that his friends and acquaintances said he was “no longer Gage.”

It was clear that Gage had undergone a profound change in his personality as a result of his injury. Several other reports exist, and they consistently state that he had permanently lost his inhibitions, had taken to behaving inappropriately in social situations, and some even stated that he had become violent.

Gage lived on for another 12 years before dying on May 21st, 1860, aged just 36, from severe seizures.

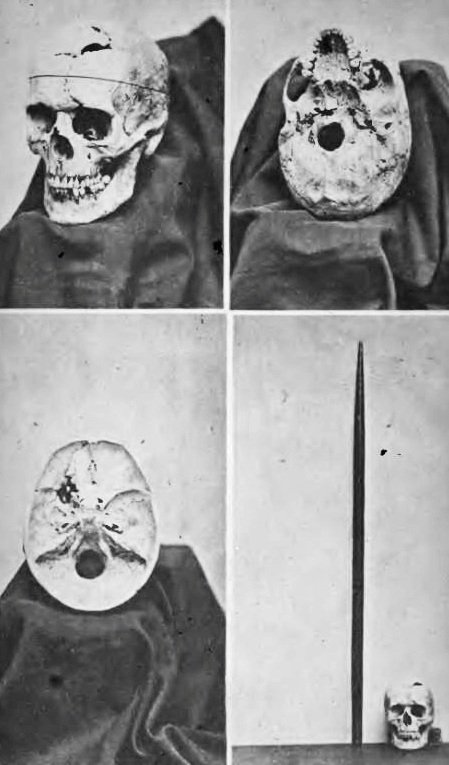

Gage’s skull and the tamping iron, displayed at the Warren Anatomical Museum in 1870

The role of the frontal lobe

In the 170 years or so that has passed since Gage’s unfortunate accident medical science has progressed considerably. We now have a very solid understanding of the role of the frontal lobe.

We use our frontal lobes to make decisions and understand the consequences of these decisions, it is where our personality is formed, and it plays a key role in our conscience. It also allows us to carry out higher mental functions, such as planning, and houses the frontal motor cortex, which regulates activities such as walking.

The accident and improbable survival of Phineas Gage was the first step on the road to our understanding of the frontal lobe and paved the way for many of the advances in Neuroscience that have occurred since.

Recent Comments