In the Spring of 2009, a new strain of influenza began to infect people in Mexico. Reports suggested that the outbreak had started in February due to farming practices at a pig farm and it was henceforth given the name ‘swine flu’. By April, cases had started to spread and were appearing in the United States and other countries.

At the time I was working as an Emergency Medicine Registrar and I can clearly recall the sensationalized press reports that were being printed. As the cases increased in number there was a palpable sense of panic. I had worked through the SARS outbreak a few years earlier, which had also received a great deal of media attention, so I was not unaccustomed to this sort of scenario.

By the autumn, cases were becoming more widespread in the UK and I was one of the first clinicians to contract the illness at the Hospital where I was working. I spent a few days in bed with high fevers, joint pains and an annoying cough but made a quick recovery and was back working shifts a week or so later.

On August 10th 2010 the pandemic was declared as being over by the WHO. The death toll for the 2009 swine flu pandemic was recently estimated as being around 284,500 people. It has been established that swine flu was caused by the H1N1 strain of influenza, the same strain that caused the most devastating pandemic in human history, the 1918 outbreak better known as ‘Spanish flu’.

The aftermath of the Great War

Between July 1914 and November 1918, Europe and much of the rest of the World would be ravaged by one of the deadliest conflicts in history, World War I. For four years both sides would be locked in a tactical stalemate caused by the advent of trench warfare. By 1918 much of world was suffering food shortages and malnutrition. The most profoundly affected were the soldiers, and disease flourished in the trenches, with typhus, malaria and trench foot being commonplace.

In the spring of 1918 people started to fall ill with flu. The initial wave of the illness was not too different to a standard flu epidemic but later that year in August 1918 a second wave hit. This time large numbers of soldiers were beginning to fall ill with a much nastier version of the flu. Death rates were alarming and reports of the illness were censored by the most of the major powers involved in the conflict including Britain, France, the United States and Germany. Spain was a neutral country during World War I and their press was free to report on this new illness. It caught the attention of the Spanish people when King Alfonso contracted it and became gravely ill. The uncensored reporting in Spain gave the impression that Spain was the most-affected area and for this reason, the pandemic has been referred to ever since as the ‘Spanish flu’.

By around November 1918, the number of new cases fell abruptly. Many speculate that the virus mutated to a less severe strain. A third, smaller peak occurred in early 1919 and by Spring of that year, the pandemic was over.

The three pandemic waves: weekly mortality rates in the UK from 1918-19

I had a little bird…

A striking feature of the 1918 flu pandemic was the speed and efficiency with which it spread. The extremely limited Public Health measures available at the time and lack of any effective treatment or vaccine left Physicians helpless against it.

Children at the time would skip rope to a rhyme, which alluded to its infectivity:

‘I had a little bird,

Its name was Enza.

I opened the window,

And in-flu-enza.’

The close proximity of the troops huddled in the trenches caused the flu to spread rapidly amongst them. As these troops returned home the flu spread to the general population. Increased travel and massive troop transportation during the war quickly made it a global phenomenon and the numbers of people affected were huge. One of the most alarming features of this particular flu pandemic was the unexpectedly high death rate, particularly in healthy young adults, that was associated with it.

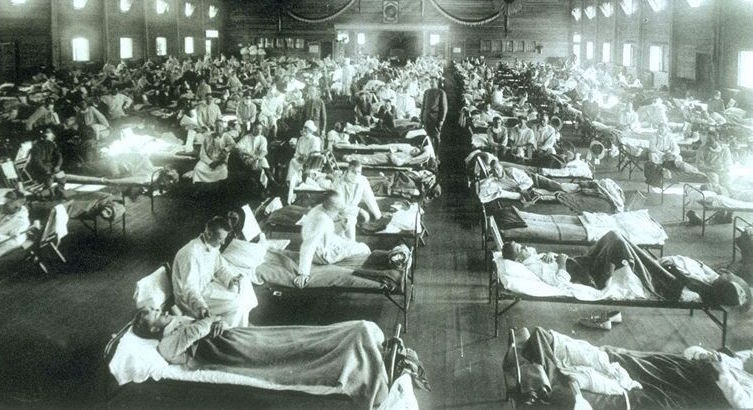

Soldiers from Fort Riley, Kansas, with Spanish flu (Photo by unnamed U.S. Army photographer)

Why did Spanish flu kill so many people?

Between 1918 and 1919 20% of the World’s population would contract the Spanish flu. The total death toll will never be known for certain but is estimated to be between 50 and 100 million, which is between 3 and 6% of the total World population at the time. This is a staggering total that makes it one of the deadliest pandemics in human history. To put this number in perspective it is thought that more people died in the year that the flu pandemic lasted than in the 4 years that the bubonic plague raged across Europe. It has also been said that more people died of Spanish flu in 24 weeks than died of AIDS in 24 years.

The symptoms were unusual also, so much so that some of the early cases were misdiagnosed as dengue, cholera or typhoid. Bleeding from the nose, ears, gastrointestinal tract and underneath the skin was reported in many cases. Some patients even died from haemorrhage within the lung itself. One observer at the time wrote that:

“One of the most striking of the complications was haemorrhage from mucous membranes, especially from the nose, stomach and intestine. Bleeding from the ears and petechial haemorrhages in the skin also occurred”

The majority of the deaths were caused by secondary bacterial pneumonia but many also died directly from the effects of the virus itself. It was a truly terrifying illness.

The pattern of morbidity and mortality was very different to other flu outbreaks. Flu is usually a killer of the very young and old, Spanish flu, however, was mostly killing those in the 20 to 40-year-old age range, the group that is usually most robust and least affected. Young pregnant women were particularly susceptible.

It is now believed that the reason that it killed so many young healthy people was because it triggered a cytokine storm. Cytokines are responsible for cell signalling and play a key role in the immune response. Cytokine storm is a phenomenon whereby this reaction becomes uncontrolled and too many immune cells are produced. This exaggerated response leads to increased inflammation in the areas affected and causes much more severe symptoms and higher mortality rates. In effect, a strong healthy immune system became a liability rather than an asset. This unusually severe form of flu killed as many as 20% of those infected, compared with a mortality rate of 0.1% for a standard epidemic.

American Expeditionary Force victims of Spanish flu at a U.S. Army Camp Hospital (Photo by unnamed U.S. Army photographer)

Where did the pandemic really start?

There has been much speculation about the true origin of the Spanish flu. We know that it did not actually originate in Spain but until recently the exact source of the pandemic has been something of a mystery.

Recent work by Canadian historian Mark Humphries may have finally solved this puzzle. Humphries has discovered records that suggest that the mobilization of 96,000 Chinese labourers to work behind the Allied lines may have been the source. The archives that he discovered show that an outbreak of a respiratory illness, that was identical to Spanish flu, occurred in northern China months earlier than the European outbreak, in November 1917. Other medical records show that over 3,000 of the 25,000 Chinese Labor Corps Workers transported across Canada to Europe in 1917 ended up in medical quarantine, many with flu-like symptoms. It may be the case that these labourers transported the influenza virus with them to the Western Front from China. Further evidence for this hypothesis has been provided by historian Christopher Langford, who has shown that China suffered a lower mortality rate from the Spanish flu than other nations did. This could possibly be due to immunity in the population from earlier exposure to the virus.

Lessons from the past

Every year we are subjected to new flu epidemics and lives are lost. The World Health Organisation is constantly on the lookout for signs of a new deadly outbreak. Medical science has progressed tremendously over the past 100 years and we are better prepared than ever before to deal with a pandemic with public health measures, antivirals, antibiotics and vaccines. But global travel and the spread of disease have never been easier and the next swine flu or SARS epidemic may be just around the corner. Hopefully, when the next pandemic breaks, the lessons we have learned from Spanish flu will help us to control it.

Recent Comments