“The good physician treats the disease; the great physician treats the patient who has the disease.” – Sir William Osler

The name Osler is very familiar to most medical students and doctors. Osler is widely regarded as ‘The Father of Modern Medicine’ for his pioneering work in medical assessment, diagnosis and education. He also lent his name to an extensive range of medical signs, diseases and techniques, and remains a very famous figure to this day. He was also a bibliophile, historian, author and a renowned practical joker.

Early life and medical training

Osler’s father, Featherston Lake Osler, was a former Lieutenant in the Royal Navy who served on HMS Victory. His mother, Ellen Free Pickton Osler, was a profoundly religious lady, and this would have a strong influence on him throughout his childhood. Featherstone retired from the Navy in 1837, and the couple emigrated to Canada, where he would establish a small church and become a minister.

Osler was born on 12th July 1849 in a remote part of Ontario, Canada, known as Bond Head. He was named after the former King of England, William of Orange, who won the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. He was a boisterous and outgoing child, with a great love of practical jokes. On one occasion he locked a flock of Geese in a schoolroom, and on another, he removed all of the desks and benches from a classroom. These antics would end up landing Osler in trouble, however, and he was briefly expelled from Grammar school in Dundas Ontario.

His parents were keen for him to follow in his father’s footsteps and were keen for him to train for the ministry. In 1866, aged sixteen, he enrolled at Trinity College, Toronto to help prepare him for this path. While at Trinity College, Osler would meet one of his greatest influences, the Reverend William Arthur Johnson, who introduced him to the world of science and natural history. This meeting would change his direction in life and ultimately resulted in him studying medicine. Osler describes his relationship with Johnson 50 years later:

“Imagine the delight of a boy of an inquisitive nature to meet a man who cared nothing about words, but who knew about things – who knew the stars in their courses and could tell us their names, who delighted in the woods in springtime, and told us about the frog spawn and the caddis worms, and who read us in the evenings Gilbert White [a popular naturalist] and Kingsley’s “Glaucus,” who showed us with the microscope the marvels in a drop of dirty pond water, and who on Saturday excursions up the river could talk of the Trilobites and the Orthoceratites and explain the formation of the earth’s crust.”

Medical training and early career

This introduction to the world of science would ultimately stimulate an interest in the field of medicine, and in 1868, he enrolled at Toronto Medical School. He transferred to McGill University, in Montreal in 1870, and was awarded his medical degree there in 1872.

After qualification as a doctor, Osler travelled in Europe to gain more hands-on training. He trained in London, Vienna, and in Berlin. During his travels, he spent time studying under the famous Rudolf Virchow in Germany, and in the physiology laboratory of John Burdon-Sanderson at University College London. In 1873 he discovered he became the first person to identify a new type of blood corpuscle, which would subsequently become known as platelets.

He returned to Montreal in 1874, where he was appointed to the medical faculty at McGill University. One year later he was promoted to the position of Professor of Medicine, aged just 26. At McGill, he taught medicine, physiology and pathology. In 1884 he moved to the University of Philadelphia in the United States and became the chair of clinical medicine there. While in Philadelphia he became one of the seven founding members of the Association of America Physicians, a society dedicated to ‘the advancement of scientific and practical medicine.’

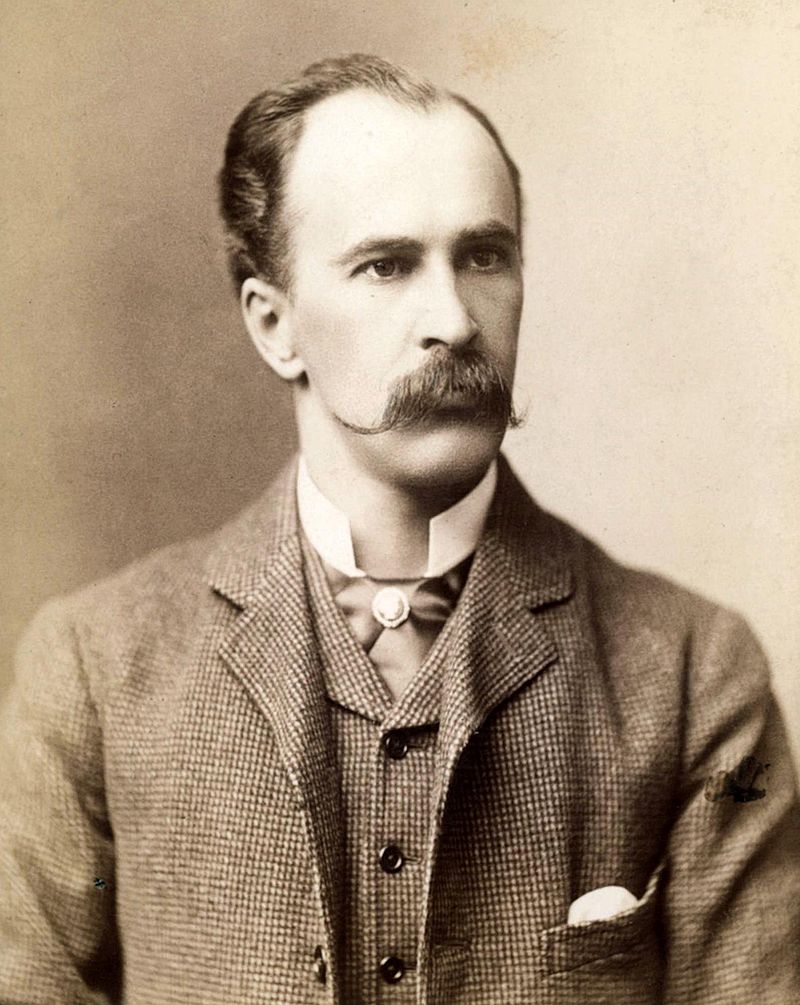

William Osler, pictured in 1880

Johns Hopkins University

In 1873 the wealthy Baltimore merchant banker and philanthropist Johns Hopkins died and left a sum of $7,000,000 to establish a new hospital and university in his name. Sixteen years later, in 1889, the Johns Hopkins Hospital would finally open, and four of the most notable physicians of the time had been recruited to lead the way. These became known as the “big four”, each of them a larger than life personality; pathologist William Henry Welch, surgeon William Halstead, gynaecologist Howard Kelly, and, of course, William Osler.

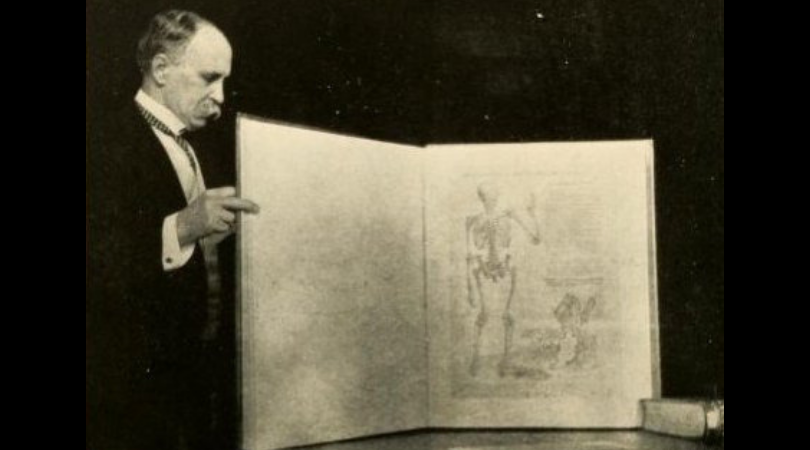

Osler was appointed as Physician-in-Chief and was instrumental in the establishment of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, which opened in 1893. In 1892 Osler published ‘The Principles and Practice of Medicine’, which was based upon the advances in medical science of the previous fifty years, especially the germ theory of disease. This book became the most famous medical text of the day, and remained the standard text on clinical medicine for the next forty years, and remained in print until 2001.

Shortly after the publication of ‘The Principles and Practice of Medicine’, Osler married Grace Revere Gross, the great-granddaughter of Paul Revere, and the widow of Dr Samuel W. Gross. They had two children together: the first son, born in 1893, died soon after birth. Their second son, Revere, died on the battlefields of World War I. Osler wrote in his diary when he heard the news:

“The War Office telephoned at 9 in the evening that he was dead. A sweeter laddie never lived, with a gentle and loving nature. We are heartbroken, but thankful to have the precious memory of his loving life. Fates do not allow the good fortune that has followed me to go with him to the grave – call no man happy until he dies.”

Contributions to medical education

Perhaps Osler’s most notable achievements at Johns Hopkins were his revolutionary contributions to medical teaching and training. For the first time, he took medical education out of the lecture theatre and brought it to the bedside. His student ward rounds became legendary, and he showed great humility too, often using his own clinical errors as teaching examples. This famous quote by Osler shows the level of importance he placed on learning in a clinical setting:

“Medicine is learned by the bedside and not in the classroom. Let not your conceptions of disease come from words heard in the lecture room or read from the book. See, and then reason and compare and control. But see first.”

He also established the very first residency program for post-graduate doctors. The hierarchical structure of the residency program proved to be a perfect learning environment for young trainee doctors. The resident would work in a full-time, sleep-in system, usually living in the administration building of the hospital. Doctors would spend as long as seven or eight years working in this way before graduating to a more senior position. This system of residency proved to be so successful that numerous other teaching hospitals adopted it at the time and it subsequently spread across the English-speaking world. It remains in place today, and I worked in a similar system as a junior doctor in the early 2000s in London.

Later life and death

Osler visited England in 1904, and while there he was invited to succeed Sir John Burdon Sanderson as the Regius Chair of Medicine at Oxford University. He accepted the position and moved to England. While at Oxford he taught just once a week and reduced his clinical duties considerably.

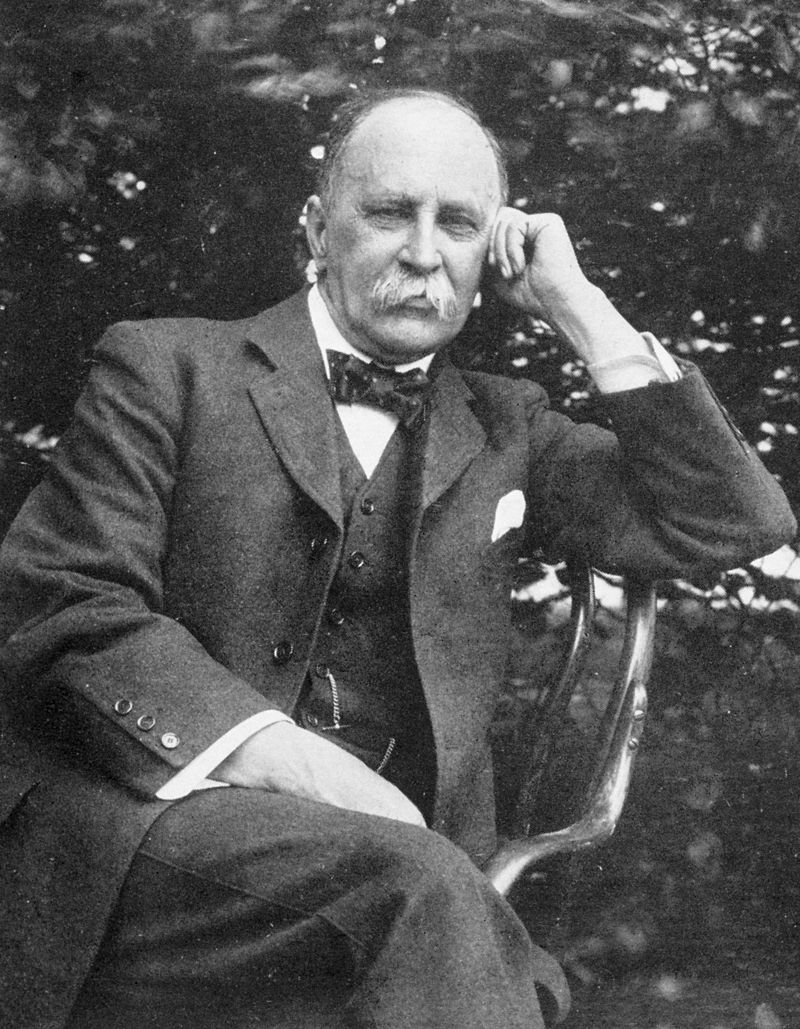

William Osler pictured in 1912, images sourced fromWikipedia

Courtesy of Materialscientist CC BY-SA 4.0

In 1919 Osler’s health would wane, and he developed a severe case of pneumonia. He died on December 29th 1919 from an empyema complicating his pneumonia. Few physicians have influenced the face of modern medicine as much as Osler did. He will forever be immortalised in the medical world through the ground-breaking changes to medical training and education he implemented, and also through the large number of medical eponyms associated with his name.

“The practice of medicine is an art, not a trade; a calling, not a business; a calling in which your heart will be exercised equally with your head. Often the best part of your work will have nothing to do with potions and powders, but with the exercise of an influence of the strong upon the weak, of the righteous upon the wicked, of the wise upon the foolish.”

Recent Comments