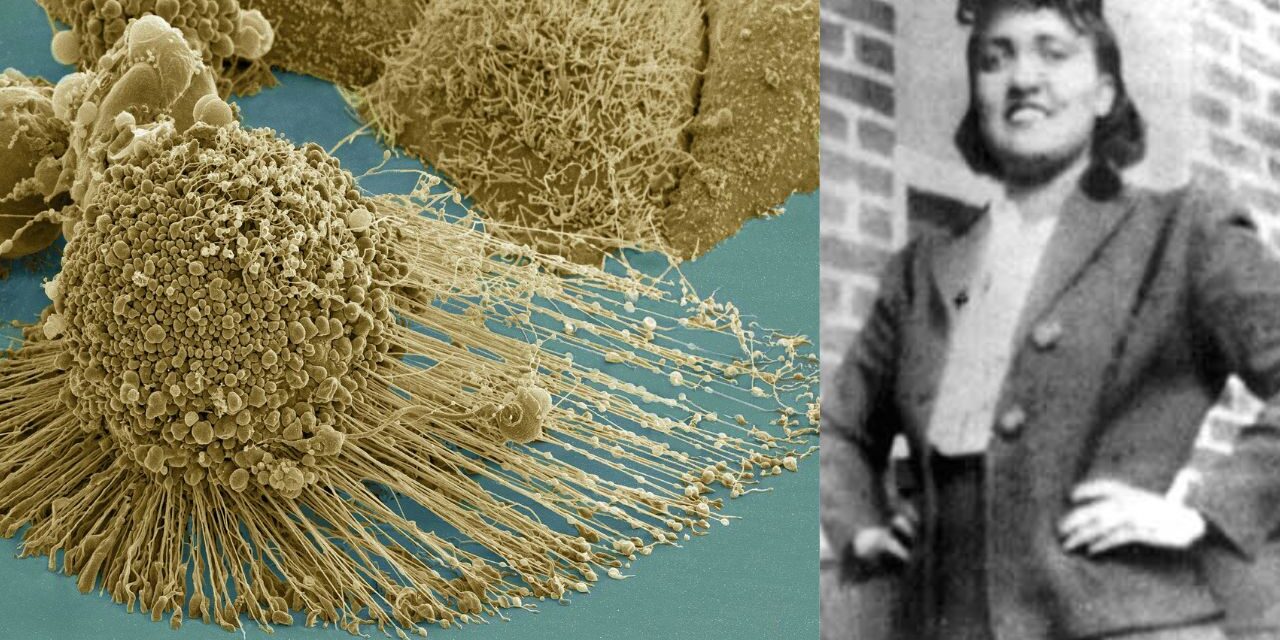

On January 29th, 1951, a young African-American woman named Henrietta Lacks presented to the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. She had been experiencing discomfort in her abdomen, which she described as a “knot” in her womb. Four and a half months earlier, she had given birth to her fifth child, Zakariyya, and had suffered a severe postpartum haemorrhage. The doctor who assessed her that day discovered a mass on her cervix and took a biopsy, and subsequently discovered that she had cervical cancer. Lacks was treated with radium tube inserts, and during her course of treatment, two more tissue samples were taken from her cervix, both without her permission or knowledge. The cancer quickly metastasised, and a few months later, on October 4th, 1951, she passed away, aged only 31. Unbeknown to anyone at the time, this tragic illness would herald one of the most ground-breaking and controversial scientific discoveries of the 20th century.

A photo of Henrietta Lacks taken sometime in the late 1940s

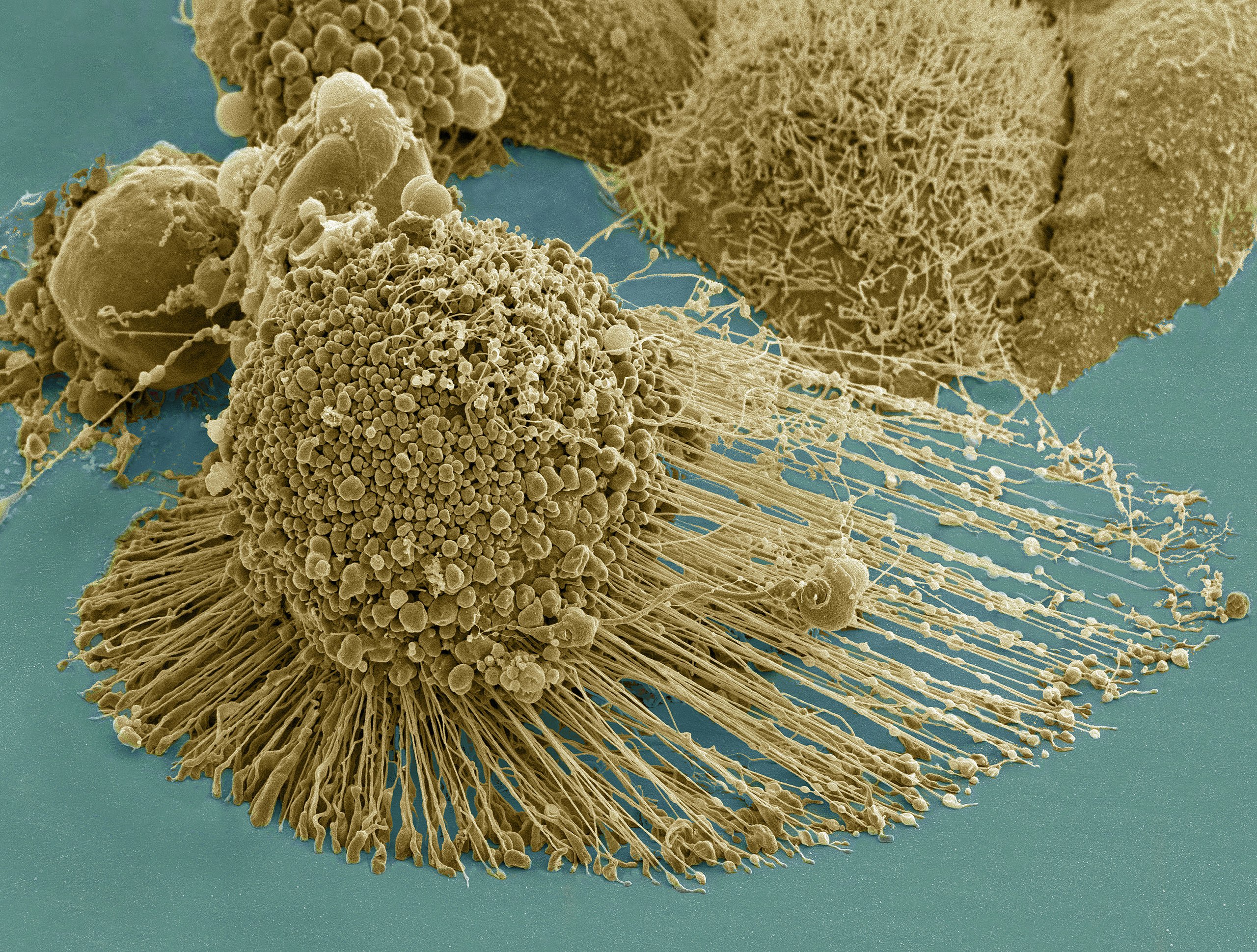

The HeLa cells

The tissue samples taken from Henrietta Lacks during her treatment were passed on to the cancer researcher George Otto Gey. One of the samples was of healthy tissue and the other contained cancerous cells. Her cancer was incredibly aggressive, and Gey noticed that the cells were unusual because they reproduced at an astonishingly high rate and could be kept alive long enough to perform very in-depth examinations. Until that point, cells cultured for laboratory studies survived for a few days at most, which was not long enough to perform any meaningful analysis or tests. It became apparent that these cells could, in fact, divide multiple times without dying, and for this reason, they became known as ‘immortal”.

George Otto Gey (Photo Fair Us from Wikipedia)

Gey then acquired more samples from Henrietta’s body at the Johns Hopkins autopsy facility. Using cells from these tissue samples, Gey was able to establish a cell line by isolating one specific cell and repeatedly dividing it. This meant that the same cell could be used repeatedly to conduct research and experiments. This cell line became known as the HeLa cells because Gey’s standard method for labelling samples was to use the first two letters of a patient’s first and last name.

Scanning electron micrograph of an apoptotic HeLa cell

An astounding scientific discovery

The discovery of this immortal cell line would become one of the most important scientific discoveries of the 20th century. The HeLa cells were truly remarkable, and when word spread of them, they became in high demand in the scientific community. The cells were put into mass production and mailed out to scientists worldwide.

One of the very first scientific discoveries made using the HeLa cells was the polio vaccine. In 1954, Jonas Salk tested his new vaccine on HeLa cells that were mass-produced in the first-ever cell production factory. At the time, polio was a devastating disease, affecting mainly children. Polio attacks the nervous system and can lead to spinal and respiratory paralysis and, in some cases, death. By the mid-20th century, polio killed or paralysed over half a million people yearly. Many who survived faced lifelong consequences, some requiring leg braces or wheelchairs, and the worst affected needing an artificial respirator called the ‘iron lung’ to survive. In April 1955, Salk’s vaccine that was tested using the HeLa cells was licensed for use, and five years later, only 161 global cases remained.

HeLa cells would go on to be used in many more medical and scientific discoveries in the years that followed and are still used today. Notably, they have been used in research into cancer, AIDS, numerous vaccines, the effects of radiation, IVF treatment, and gene mapping. They have even been used to study the effects of zero gravity in space travel.

Consent and controversy

Consent means a person must give permission before any form of treatment, test or examination is performed. This must be done based on an explanation by the clinician or scientist performing it. Informed consent is a mainstay of modern medical practice and one of the founding principles of research ethics. Neither Henrietta Lacks nor her family gave the doctors treating her permission to harvest her cells. This was not unusual in the 1950s, however, when permission was not a legal requirement.

In 1975, a large proportion of other cell cultures became contaminated by HeLa cells. Following this, Henrietta Lack’s family started to become inundated by phone calls from researchers asking for blood samples. These research scientists hoped these samples could help differentiate between HeLa cells and the other cell lines. The family, however, were entirely in the dark about what was happening and became distressed by these seemingly bizarre phone calls. It was not long before the family became aware that Henrietta’s cells had been harvested and used without her permission. To make matters even worse, the family’s medical records were published without consent in the 1980s.

The story came into the public spotlight in 2010, when author Rebecca Skloot published her book on the story “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks”. The publication of this book started some much-needed discussion around the ethical considerations and safeguarding of donors and their families. In 2013, an agreement was finally reached between Henrietta’s family and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) that gave the family some control over access to the cells’ DNA sequence.

The controversy surrounding HeLa cells is ongoing, however, and in October 2021, the Lacks estate filed a lawsuit against Thermo Fisher Scientific for profiting from the HeLa cell line without consent.

Progress in bioethics

Informed consent started to become more widespread in medicine and research in the early 1990s, and bioethics has been studied greatly over the past few decades.

Researchers today now follow a much stricter set of standards, and the rules of informed consent and privacy of information are very clearly set out. The lessons learned from the story of Henrietta Lacks have been very instrumental in this important progress. The legacy of Henrietta Lacks is now widely recognised, and in 2014 she was inducted into the Maryland Women’s Hall of Fame. The 1st Saturday in August each year is now designated as “Henrietta Lacks Day”, and her story was made into an HBO movie starring Oprah Winfrey in 2017.

Recent Comments