Nearly all of us know at least one person that has diabetes. The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that over 382 million people worldwide currently have diabetes. Diabetes prevents the body from effectively converting carbohydrates in food into energy, resulting in grossly elevated blood sugar levels. It is a serious condition that causes many health-related complications, but it can now be managed effectively, and many people with it lead full and healthy lives. There are two types of diabetes, type 1 and type 2, and in type 1 diabetes, the pancreas fails to produce insulin.

Type 1 diabetes can be treated with the administration of daily insulin injections, but this was not always the case, and before the discovery of insulin it was a virtual death sentence for people suffering from it. Life expectancy was short, and there was little that doctors could do to help. Adults typically lived for less than two years after diagnosis, and in children, the average life expectancy was less than a year. The suffering experienced by those that were afflicted was severe, with blindness, stroke, kidney failure, loss of limbs, and heart attacks all commonly occurring in the period leading up to the patient’s death.

Paul Langerhans and the pancreas

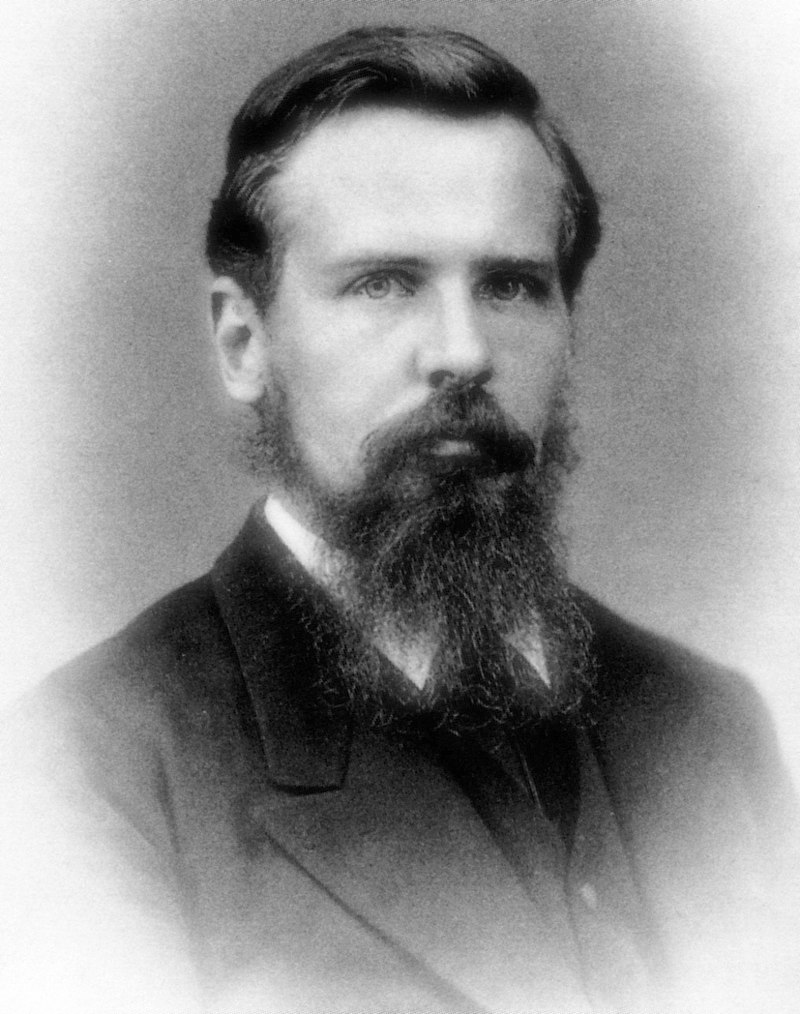

During the mid-1800’s the scientific community began to develop an understanding of diabetes. A pivotal event occurred in 1869 when a young German medical student by the name of Paul Langerhans discovered clusters of cells in the pancreas. These cells would go on to be named the islets of Langerhans after him.

Paul Langerhans in 1878

This important discovery was followed by further experimentation, and in 1889 two German physicians, Oscar Minkowski and Joseph von Mering removed a dog’s pancreas in an attempt to discover its function. It was noticed afterwards that the dog urinated on the floor frequently, despite previously being well house trained. Mering recognised that this symptom was consistent with diabetes and tested the dog’s urine. High levels of sugar were found in the urine, confirming his suspicions. Minkowski and von Mering had discovered that the pancreas contained some form of a regulator that controlled blood sugar levels.Finding out precisely what this regulator was would prove to be difficult though, and decades would pass before it would be successfully extracted.

Further clues would be provided by an American medical student called Eugene Opie in 1901 when he noted the presence of consistent morphological alterations in the islets of Langerhans in patients with diabetes. Just over a decade later in 1916, a Romanian physiologist called Nicolas Paulescu would extract a substance from the pancreas, which normalised blood sugar levels after being injected into a dog with diabetes. World War I prevented his experiments from continuing though, and unfortunately, his work was largely overlooked.

The starvation diet

In the early 1900s, the only treatment available for type 1 diabetes was the ‘starvation diet’. This diet was devised by an American physician named Frederick Madison Allen. He had observed that on a low-carbohydrate diet that he referred to as the Eskimo diet, dogs with diabetes remained relatively well.

Between 1915 and 1922 many patients were treated with a diet based on repeated fasting and prolonged undernourishment, with most patients ingesting less than 500 calories per day. Whilst this diet did reduce blood glucose levels in diabetics, and also reduced the incidence of complications and prolonged life expectancy by a couple of years, it also came with a host of new problems. The quality of life for those on the diet was awful, and patients became emaciated, some even dying from starvation. This ‘starvation diet’ was clearly not a long-term viable option for the treatment of diabetes.

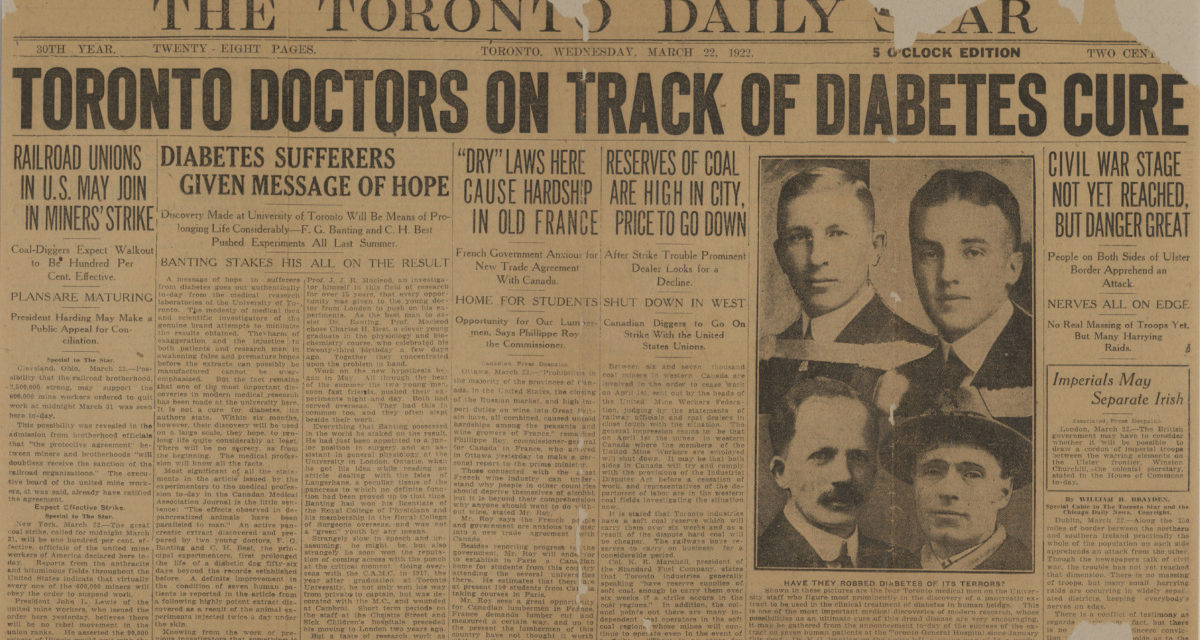

Banting and Best

Everything would change for diabetics in the 1920s with the work of a young Canadian orthopaedic surgeon named Frederick Banting, and his medical student assistant Charles Best. Between 1920 and 1921, Banting and Best removed the pancreas from dogs in an attempt to make them diabetic. They then sliced up the pancreas of one of these dogs and ground it into a thick brown injectable extract, which when administered to the dog, reversing the symptoms of diabetes and the presence of sugar in the dogs urine. They repeated this experiment in another dog with severe diabetes and kept it alive for 70 days, before the extract ran out and the dog eventually died.

The work of Banting and Best was being overseen by a Scottish professor of physiology called J.J.R. MacLeod, who was impressed with their work but felt that further evidence was required. Macleod freed a biochemist called James Collip from his other research commitments to assist them in the purification of this pancreatic extract, and together the team would successfully purify the substance they named ‘insulin’ and ready it for use in humans.

The first humans in which insulin was tested upon were Banting and Best themselves. They injected themselves with it and developed symptoms consistent with low blood sugar levels.

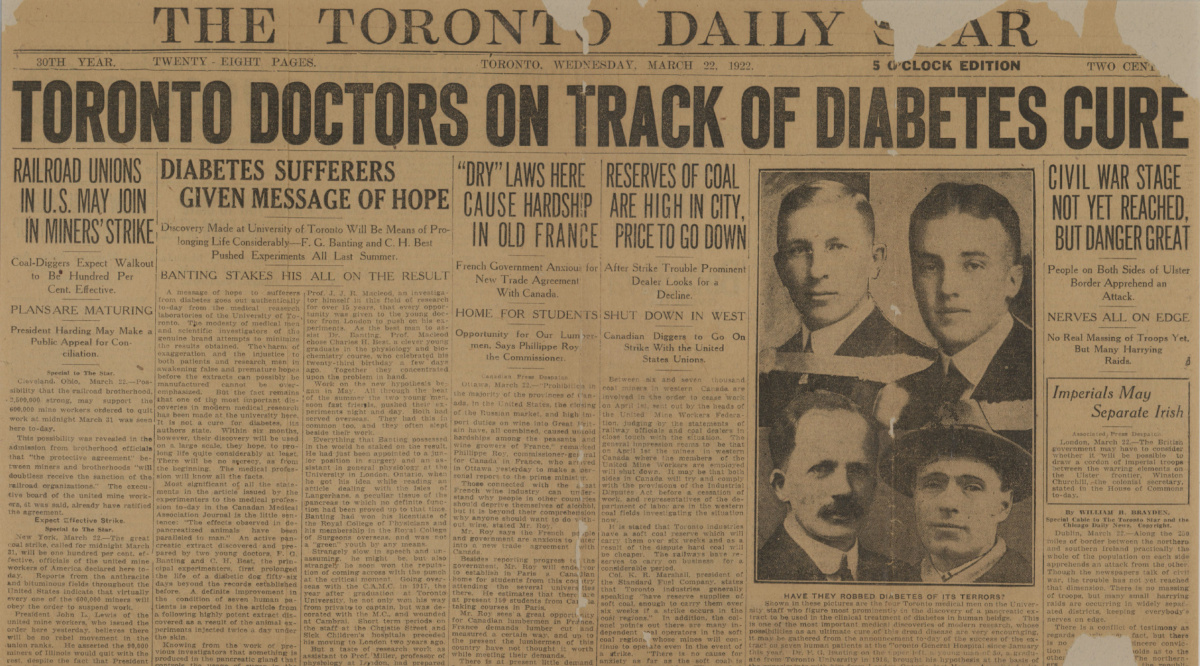

The front page of the Toronto Daily Star on March 22nd, 1922

Leonard Thompson – the first human patient

In 1922, a 14-year-old boy named Leonard Thompson lay in bed in Toronto General Hospital suffering from severe diabetes. He weighed less than 30 kg at the time and was given a just a few weeks to live. Realising the severity of his son’s condition, Thompson’s father consented to him being injected with this new experimental treatment called insulin.

The first injection did not go as planned, and Thompson developed an allergic reaction that was most likely caused by an impurity in the extract. Undeterred, Collip refined the extract and administered a second dose 12 days later. Thompson showed signs of improved health almost immediately and made a remarkable recovery. He would go on to live another 13 years, before dying of pneumonia aged 27.

News of this miracle cure spread rapidly, and before long Banting and Best were receiving letters from other diabetics asking for help. By the end of 1922 production techniques were improved and Eli Lilly became the first large-scale insulin manufacturers. In 1923 Banting and Best received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work.

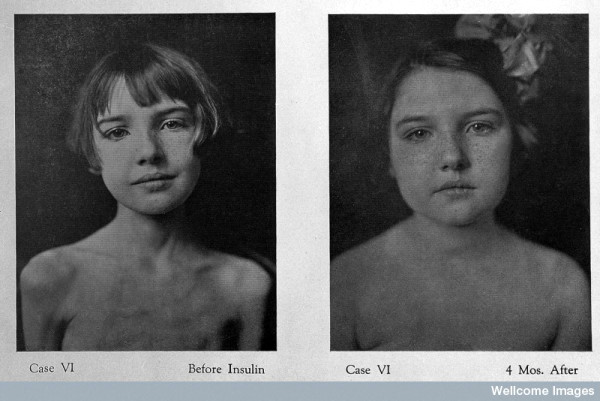

A young diabetic patient pictured before and after treatment with insulin, image sourced from Wikipedia

Courtesy of Wellcome Images CC BY-SA 2.0

A medical miracle

Over the decades that followed insulin formulations were gradually improved upon. Longer acting insulin was created in the 1930s, and in the 1970s the traditionally used pig and cow sourced animal insulin formulations were replaced by ‘human insulin’ produced using recombinant DNA techniques.

The discovery of insulin was indeed a medical miracle and patients with type 1 diabetes can now expect to have long and healthy lives. The life expectancy of a diabetic patient is now only 10 years less than that of an average person, a far cry from that of the death sentence it represented 100 years ago.

Recent Comments