Typhoid fever is a particularly nasty infection caused by the bacteria Salmonella typhi. The infection causes malaise, abdominal pain, a rash, diarrhoea or constipation, and in severe cases can result in intestinal bleeding and death. Although there are still millions of cases each year, the majority of these occur in areas where there are poor sanitation and hygiene, and typhoid is now treatable with antibiotics and preventable with vaccines.

A somewhat unusual aspect of typhoid fever is that not everyone infected with it develops symptoms. Certain people that contract it remain entirely asymptomatic, but although unaffected themselves, they can still transmit the disease to others. No name is more synonymous with the disease than that of Mary Mallon, better known as ‘Typhoid Mary’, the first identified typhoid carrier in the United States.

‘Typhoid Mary’ in a 1909 illustration that appeared in The New York American

The early life and career of Mary Mallon

Mary Mallon was born on September 23rd, 1869 in Cookstown, Ireland. Little is known about her early life, but she is known to have emigrated to the United States in either 1883 or 1884. Like the majority of Irish immigrants at that time she initially found work as a domestic servant. With time it became apparent that she had a talent for cooking, and around 1900 Mallon started to work as a cook for affluent families in the New York area.

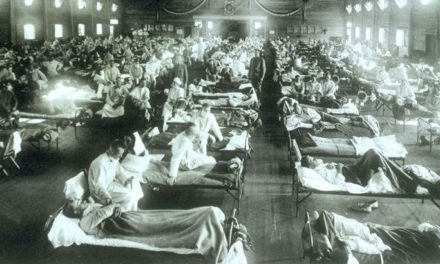

Between 1900 and 1907 she worked for several families and a strange pattern developed that wherever Mary worked people within the household would develop typhoid fever. This was unusual as in the early 1900s in the United States, typhoid fever mainly affected poor urban communities, but these households were affluent, and doctors practising in the area at the time were surprised by the demographics of these cases.

In 1906 Mallon took a position in Oyster Bay, Long Island, working for a wealthy banker called Charles Warren. On August 27th, 1906, one of Warren’s daughters fell ill with typhoid fever, and within a few weeks, 6 out of the 11 people residing in the household had fallen ill with typhoid fever.

The investigation of George Soper

The Warrens had hired the home in Oyster Bay from George Thompson and his wife. The Thompsons were shocked by this outbreak and became anxious that their water supply might be contaminated. Concerned that they would not be able to rent the property again without first discovering the source of the typhoid outbreak, they hired a local sanitation engineer called George Soper, who had experience investigating similar cases.

Soper initially hypothesised that freshwater clams were responsible and methodically interviewed the affected members of the household to see if they had eaten them. He soon discovered that this was not the case though, as not everyone stricken had eaten them. His suspicion quickly shifted to the household’s cook Mallon, and he began to track her movements and investigate her. Soper discovered that Mallon had worked for eight other families in the New York area as a cook and that seven of these eight families had experienced cases of typhoid. A total of 22 people in these households had contracted the illness, including a young girl that had died. Soper decided that this was far more than a coincidence and decided to attempt to obtain blood, urine, and faeces samples from her.

In the spring of 1907, Mallon was in the employment of the Bowen family and Soper approached her there to get the samples he needed to prove his hypothesis. Soper later described this fiery encounter as follows:

“I had my first talk with Mary in the kitchen of this house. I was as diplomatic as possible, but I had to say I suspected her of making people sick and that I wanted specimens of her urine, faeces and blood. It did not take Mary long to react to this suggestion. She seized a carving fork and advanced in my direction. I passed rapidly down the long narrow hall, through the tall iron gate, and so to the sidewalk. I felt rather lucky to escape.”

Soper tried on one further occasion to persuade Mallon to cooperate and provide samples but was once again greeted by a violent outburst. He then decided to hand over his research and notes to the New York City Health Department, and the doctor appointed to the case, Dr. Sara Josephine Baker, eventually managed to forcibly take Mallon to the Willard Parker Hospital in New York to be examined. Baker later described the dramatic events of the day:

“Mary was on the lookout and peered out, a long kitchen fork in her hand like a rapier. As she lunged at me with the fork, I stepped back, recoiled on the policeman and so confused matters that, by the time we got through the door, Mary had disappeared. ‘Disappear’ is too matter-of-fact a word; she had completely vanished.”

After searching the house Dr. Baker and the Police quickly realised Mallon had fled to the house of a neighbour, and they tracked her to a closet there, where she was hiding:

“She came out fighting and swearing, both of which she could do with appalling efficiency and vigor. I made another effort to talk to her sensibly and asked her again to let me have the specimens, but it was of no use. By that time she was convinced that the law was wantonly persecuting her, when she had done nothing wrong. She knew she had never had typhoid fever; she was maniacal in her integrity. There was nothing I could do but take her with us. The policemen lifted her into the ambulance and I literally sat on her all the way to the hospital; it was like being in a cage with an angry lion.”

Samples were taken later at the Willard Parker Hospital, and Salmonella typhi was found to be present in her stool. The first asymptomatic carrier of typhoid had been discovered. In 1907 over 3000 people in the New York area had contracted typhoid fever, and it is believed that Mallon was the main reason for the outbreak.

Dr. Sara Josephine Baker, pictured in 1922

Quarantine and the later life of Mary Mallon

Following this discovery, Mallon was taken to the Riverside Hospital on North Brother Island, where she was placed under quarantine. Throughout her period of quarantine, Mallon would persistently declare her innocence, declaring that she had never suffered from typhoid and could therefore not have been responsible for the outbreak. After two years at the Riverside Hospital, she decided to sue the New York Health Department.

Mary Mallon at the Riverside Hospital during her first period of quarantine.

The judge appointed to the case ruled in favour of the health department, and Mallon was returned to Riverside until 1910 when a new health commissioner decided to allow Mallon to go free on the condition that she would never work as a cook again. Mallon was released from her first period of quarantine on February 19th, 1910.

Initially, Mallon worked as a laundress, but she increasingly found it difficult to find work and support herself. After a couple of years, she changed her name to Mary Brown and began to work in kitchens again. Soper began to track her movements again and wherever she worked there were cases of typhoid, but she frequently changed jobs and moved, and he was unable to track her down.

In January 1915, a major outbreak of typhoid occurred at the Sloane Maternity Hospital in Manhattan. Mallon, still posing as Mary Brown, was working as a cook at the hospital during the outbreak. Twenty-five people contracted typhoid in this outbreak, and two died. She fled once again, but this time was quickly tracked down by the Police and arrested. Following her arrest, she was returned to Riverside and would remain quarantined there until she died of pneumonia, aged 69, on November 11th, 1938.

An autopsy performed following her death discovered evidence of the Salmonella typhi bacteria living in her gallbladder; she had remained a carrier until the day she died.

Recent Comments