There are few figures in medical history as troubled as William Halsted, a man who has been referred to as “the most innovative and influential surgeon the United States has produced” and also the “father of modern surgery”. He was one of the greatest surgeons of his era and revolutionised surgical training but was also a notorious drug addict. Halsted was a larger-than-life personality, and his life story is nothing short of fascinating.

The early life of William Halsted

William Halsted was born on 23 September 1852, in New York City, the son of William Mills Halsted Jr, a local businessman, and Mary Louisa Haines. Halsted’s family was a very wealthy one of English heritage, and they had two homes in New York State, one on Fifth Avenue and the other a large estate in Westchester County.

He was noted as being an average student and was educated at home until 1862, when he was sent to boarding school in Monson, Massachusetts. After graduating, he entered Yale College, where he achieved little academically, but was an excellent sportsman, captaining the football team and scoring the winning goal in the 1873 Yale versus Eton match, the first game ever with eleven players. Towards the end of his time at Yale, he developed an interest in medicine, attending medical lectures and spending time studying anatomy and physiology. He graduated in 1874 and entered the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons.

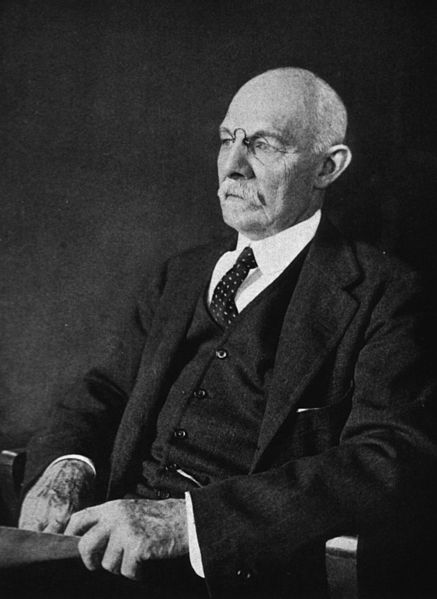

William Halsted, photograph taken in 1874.

The medical education of William Halsted

After entering medical school, Halsted left his early academic mediocrity behind him and emerged as an exemplary student with a high aptitude for medicine. Towards the end of his medical training, he took a competitive exam for an internship at the Bellevue Hospital in New York. He scored highly in the exam and was awarded the internship for House Surgeon at Bellevue for the following year. It was during this time that he was introduced to Joseph Lister’s antiseptic surgical theories and techniques, which would significantly influence his surgical practice throughout his career. He graduated from medical school in 1877, situated in the top position in his class.

After his graduation, Halsted travelled to Europe, where he would study extensively under the famous German surgeon Theodor Billroth in Vienna. After two years in Europe, he returned to New York and quickly built an illustrious reputation and a flourishing surgical practice that necessitated his services at six hospitals.

Surgical excellence

Halsted was an extraordinary surgeon, renowned for his slow, meticulous nature in the operating theatre and his unusually gentle handling of body tissues. He revolutionised surgery by relying on skill and technique instead of the brute force used by many of his peers. Halsted was often boldly experimental with the procedures that he carried out and developed numerous new surgical techniques and procedures including the radical mastectomy for breast cancer, and operations for hernias, goitres, aneurysms and a variety of gastrointestinal diseases.

In 1881, aged just 29, he was called to see his sister who was unwell after the delivery of her first baby. Halsted found her in a desperate condition having suffered a severe postpartum haemorrhage. He managed to stop the bleeding, but the blood loss already suffered was so severe that her death was imminent. Realising this, he plunged a needle into his arm and gave her a direct blood transfusion of his own blood. This is thought to have been the first blood transfusion performed in the United States. The treatment he gave her proved to be successful, and her life was saved.

His sister was not the only family member that he treated, and a year later in 1882, he performed one of the first gallbladder operations ever conducted in the United States. Remarkably the patient this time was his mother, and he performed the surgery on his kitchen table at home at 2 am. He removed seven gallstones from his mother, and she also went on to make a full recovery.

Struggles with addiction

Halsted was fascinated by the numerous advances in anaesthesia that were occurring at the time. In 1884, he read a report by the Austrian ophthalmologist Karl Koller describing the anaesthetic properties of cocaine when instilled on the surface of the eye. Intrigued by the potential of this new anaesthetic agent, Halsted started to experiment with it himself. He discovered that an injection of cocaine into a major nerve trunk could anaesthetise an entire limb or even block the spinal cord. These discoveries would pave the way for modern regional and spinal anaesthesia.

Unfortunately, Halsted performed many of the experiments with cocaine on himself and would inject it into himself before using on his patients in surgery. As a consequence of this self-experimentation, he became hopelessly addicted to it. His work began to suffer, he was caught lying, missed days at work and descended into a spiral of inconsistency and self-destructive behaviour. In 1885, he published an article on cocaine anaesthesia in the New York Medical Journal that was so incoherent that any remaining trust in him as a surgeon was lost. His career as a surgeon in New York was effectively over.

After this disastrous downturn in his life, Halsted embarked on a two-week steamboat voyage in an attempt to detox from cocaine. As soon as he returned to the United States, however, he immediately fell back into addiction and was booked into the Butler Sanitorium in Providence, Rhode Island, where they attempted to cure his cocaine addiction with the administration of morphine. He successfully managed to stop using cocaine, but had traded one addiction for another, and spent the rest of life as a high-functioning morphine addict.

Resurrection at Johns Hopkins

Following his discharge from Butler, Halsted moved to Baltimore to resurrect his career by helping with the launch of the new Johns Hopkins Hospital. He would become one of the “Big Four” founding physicians at Hopkins, along with William Henry Welch, William Osler and Howard Kelly.

In 1890, Halsted was made the Surgeon-In-Chief at Hopkins, and it was here he would meet and marry the nurse, Caroline Hampton. It was thanks largely to their romance that surgeons worldwide began wearing gloves during surgery. Hampton, acting as his scrub nurse would have to handle disinfectant chemicals regularly, and as a consequence, she developed severe contact dermatitis on her hands. Halsted could not bear to see her go through this and reached out to the Goodyear Rubber Company to create a rubber glove that she could wear during surgery to protect her hands. The use of gloves spread rapidly among his colleagues after this.

It was during his time at Hopkins that Halsted would institute the first formal surgical residency training program in the United States. He based residency largely upon the German system he had encountered during his time in Europe. The system was intense and relentless, with trainee surgeons working 100 plus hour weeks in close relationship with an appointed surgical mentor. The program began with an internship of an undefined length, followed by six years as an assistant resident, and then a further two years as House Surgeon. This new system of training would spread around the United States and have a profound effect on both medical and surgical training around the world, with many aspects of it still in effect today. During his time at Hopkins, Halsted trained many notable surgeons of the era, including Harvey Williams Cushing and Walter Dandy, the co-founders of the speciality of neurosurgery, and Hugh H. Young, the founder of the speciality of urology.

William Halsted, photograph taken in 1922, shortly before his death.

Later years and death

Halsted continued his work at Hopkins for the remainder of his career. In 1919 he became unwell and underwent surgery for gallstones. The operation was performed by Dr Richard Follis, one of his former residents. The surgery was successful, but the pain and jaundice returned the following year. He continued to deteriorate, and further surgery was carried out, this time by his former Chief Resident Dr George Hauer in September 1922. This time he developed a post-operative bacterial infection, and he died on 7 September 1922.

Despite his dreadful struggles with addiction, Halsted’s legacy to medicine is unquestionable.

I find his story both inspiring and sobering. When I read about him, I’m reminded how fine the line can be between brilliance and self-destruction, and how even those who change medicine forever often do so at a great personal cost.

Recent Comments